We are surrounded by ways to make mistakes.

There are so many.

And so we err. We blunder. We learn to apologize.

But mistakes can also be made on purpose.

Sometimes that purpose is mystical. Navajo weavers introduce “spirit lines” into their rugs to stop these transcendent objects from trapping their soul.

The Japanese concept of wabi-sabi embraces the beauty in imperfection and teaches acceptance and impermanence. (The idea of designing technology that can age, passim.)

Sometimes the purpose is more earthly.

Trap streets are “cartographic fictions”—fake entries in maps, added in by the maker as a signature. China Miéville turned them into a whole world in Kraken. If you make the map, you know where the traps are; if you copy the map, you don’t spot the mistakes. You get caught.

⌘

T-rex pounds down the track, smashing through trees and roaring wildly as it hunts down the jeep. Jeff Goldblum, folded up in terror and injury, cringes back and knocks against the gearshift. Laura Dern suddenly screams “Look out!”

Did you see it?

It is easy to miss on the first attempt, or even the fifth. But keep looking, and the eye can eventually discern what the brain couldn’t: a brutal jump cut right in the middle of an action scene from one camera angle to a slightly different camera angle of the same thing.

One of the biggest movies of all time, breaking one of the most basic rules of cinematography.

⌘

There’s a line at the end of the first verse of The War on Drugs song “I Don’t Live Here Anymore” that sounds like “I never wanted anything / that someone had to give / I don’t live here anymore / I went along eeh will.”

In an episode of the Song Exploder podcast, lead singer Adam Granduciel explains: He ran out of words when he was writing and made a noise instead. Despite attempt after attempt in the studio to replace it with another line, he could never find a better answer. So it stayed.

⌘

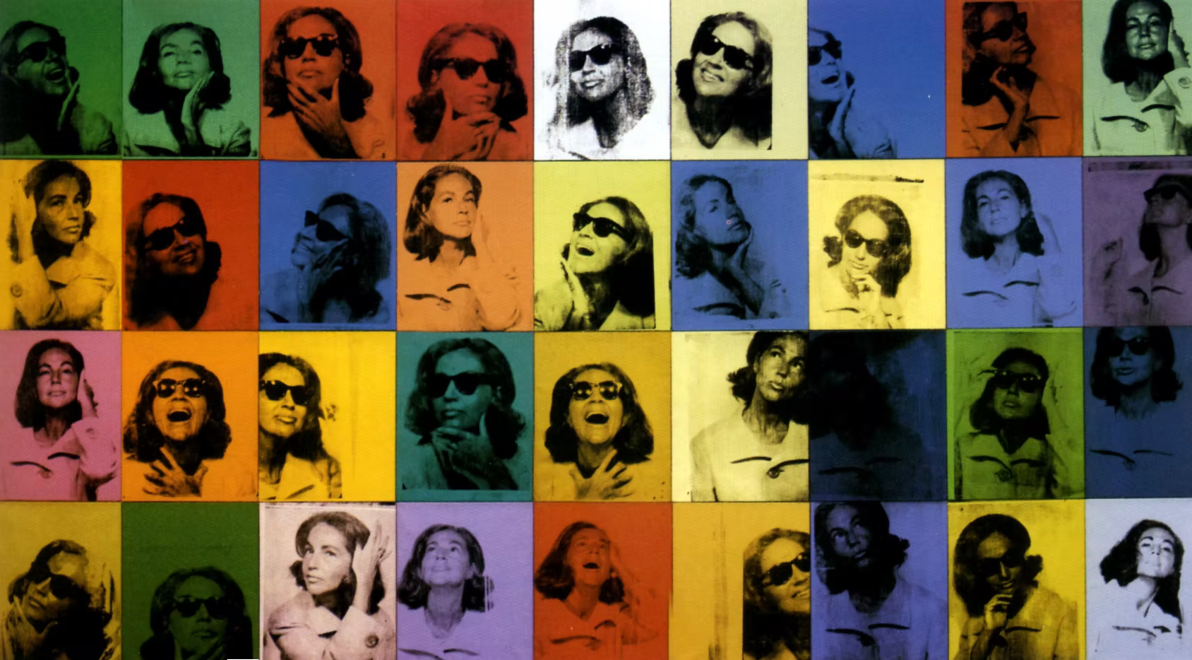

There are so many ways we can make mistakes, but also to make things that merely have the appearance of a mistake. Rug makers, musicians, film editors, map makers—all making deliberate choices to keep an error, or introduce one, in a piece of work.

They know why, just like you do. There are moments when feeling overtakes theory, and when the wrong answer is the only way to get the emotion right.