A man in Florida pleaded to guilty to selling $16 million of fake HIV drugs to pharmacies. A German museum worker was convicted of swapping expensive artworks for forgeries and then selling the originals to fund his lavish lifestyle. And it was revealed that some United Airlines had discovered counterfeit parts in some of their aircraft engines. Barely a day goes past without news of counterfeits, forgeries, pirate material, copycats, plagiarists and imposters. We can’t avoid them.

Fakes and frauds have a long history, from copycat Roman statues of Greek originals to Piltdown Man to the Hitler Diaries. In days gone by, when information was harder to come by, it was common for paintings or sculpture from elsewhere to be copied, and easy (if you chose) to pass a copycat off as an original work. Witness the Turin Shroud: is it a genuine relic or medieval fake? (And did it even matter to those who worshiped it?)

⌘

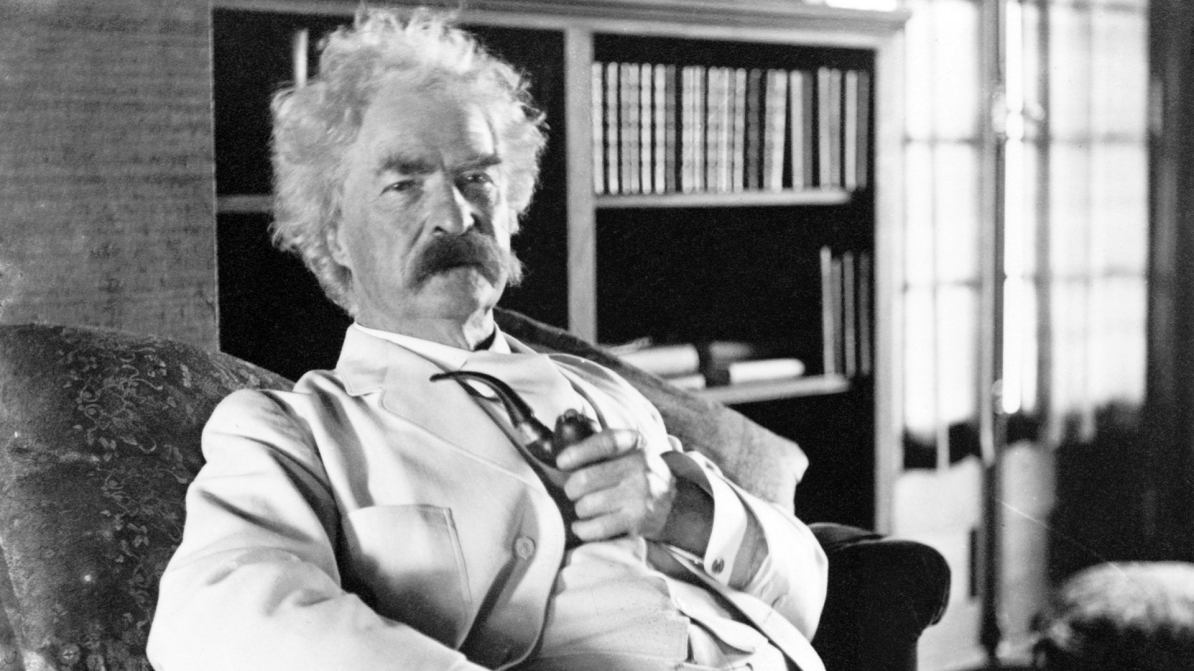

When printing arrived on the scene it enabled copying to flourish: publishers looking for a big hit would find popular books from overseas and produce their own unsanctioned copies for their local markets and reap the profits. By the late 19th century the author Mark Twain was so angry about pirate copies of his work popping up in England that he lobbied for new copyright laws and invested nearly all of his fortune into new-fangled printing technology. It almost bankrupted him.

Exploiting this information gap was something that lasted a long time, and perhaps still can, from time to time: in 1969, when “Time of the Season” by The Zombies became a chart smash, unscrupulous promoters put not one but two fake versions of the band out on tour to try capitalizing on the song’s success.

Mass manufacturing added another twist. Not only do the tools of manufacturer mean that original ideas become easier for rivals to mimic (Sony co-founder Akio Morita once said his company was lucky if it got even six months before rivals would copycat new products like the Walkman) but passing off your fraudulent version as the real thing gets easier and easier too. In fashion, particularly, where exclusive branding is part of the product, it’s big business. Fake labels. Fake clothes. Fake bags. They’re everywhere. Some estimates put counterfeit fashion at $600bn a year.

And if physical piracy is a big issue, then the digital world has shifted it up by an order of magnitude. After all, when the original artwork is merely a collection of ones and zeroes, they can be replicated perfectly and spread through new markets and distribution networks. It’s what helped Napster rise, and part of what led to Amazon’s recent influx of terrible AI-generated spam books.

⌘

It’s many years since I traveled to Shanghai to profile Jan Chipchase for Wired. Jan was—and remains—an utterly fascinating individual, but really the assignment gave me an opportunity to visit China and get a better understanding of the country’s “shanzhai” culture.

As Byung-Chul Han’s book on shanzhai puts it, the word was a term “originally coined to describe knock-off cell phones marketed under such names as Nokir and Samsing. These cell phones were not crude forgeries but multifunctional, stylish, and as good as or better than the originals.”

I was fascinated by this culture precisely because they walk the very fine line between copycats and forgeries. They have the right look, but the audience has the knowledge. When you see a shanzhai edition of Harry Potter and the Chinese Porcelain Doll most people know that it’s basically fan fiction—just as when you see a kid wearing designer-branded clothing that should cost them thousands: for the most part everybody knows they’re fake—perhaps stolen, at best. But the signals it sends are still meaningful.

That’s what I witnessed in China—a kind of forgery-as-innovation—or, as a young software developer with roots in shanzhai told me at the time: “Shanzhai products are innovative because they’re mainly aimed at niche markets… the big brands need to design for the mainstream, for the mass population.”

⌘

Fakery has taken a different turn in the years since: less about forgery and more about trust—or mistrust.

Misinformation and propaganda is spread by networks of trolls supported by fake followers and click fraud. “Fake news” became a battle cry for the Trump administration, even though, for the most part, the news wasn’t fake. And now AI—whether in text material produced by generative language models or in video deepfakes of influencers used to hawk products 24/7—has us questioning whether what we’re seeing is real at all. And there’s been a decline in fact-checking services as social media platforms scale back their efforts (in part because lots of people apparently want bad information, in part because they can’t control a problem they have exacerbated.)

So, how do we deal with fakery in this new world? And what tools do we need? The problem might not be new, but the shape of it is changing faster than we can keep up with.

Related reading

- Zombie news (September 2020)

- Mistakes on purpose (February 2022)

Pingback: “There’s a lot of trust involved” – Start here